As the climate crisis continues to develop, and with Australia poised to feel its effects faster and harder than many other places around the world, antipodean residents are more at risk than most to the acute effects of “climate anxiety”, a recently coined term for the fear brought on by climate change. But what exactly is climate anxiety? Has it been formally recognised as a medical condition and – most importantly – should it be?

As the world slowly comes to terms with the realities of climate change, conversations are gradually shifting from whether or not climate change is a legitimate concern to the scale, scope, and impact of its effects.

Having said that, recent studies have shown that Australians are twice as likely to be die-hard climate change deniers than people elsewhere in the world, despite Australia being perfectly poised to feel some of the climate crisis’ effects more quickly, acutely, and intensely than many of those other countries.

In light of this, it seems even more likely that Australians are ill-prepared to deal with one of the fastest-growing mental health challenges brought on by the climate crisis: climate anxiety, also known variously as eco-anxiety, eco-guilt, and eco-grief.

So, we thought it was high time to explain to Aussie blokes exactly what climate anxiety is, how common it is, and what exactly we should be doing about it.

What Is Climate Anxiety?

Climate anxiety, as defined by the American Psychological Association, is a “chronic fear of environmental doom”.

It is also described by Australian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht as a generalised sense of the collapse of ecological foundations and worry about our relationship with supporting environments.

How Common Is Climate Anxiety?

Recent studies show that though climate anxiety is definitely most acute in younger generations – who are going to have to live through and deal with the effects of climate change – its not a concern thats strictly limited to the young: over two-thirds of Americans experience some form of climate anxiety, according to the American Psychological Association.

Furthermore, a study published in The Lancet revealed that 84% of young adults aged 16 to 25 are at least moderately worried about climate change. While a 2021 UNICEF report estimated that one billion children will be at “extremely high risk” of chronic climate anxiety.

Though research around the mental health impacts of climate change on older generations is limited, older generations may be concerned about short-term impacts of climate change like extreme weather and poor air quality, as well as feeling responsible for the environmental situation they’ve left behind.

It’s also worth noting that climate anxiety also increases the risk of developing depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders, so its effects could be far wider and more painful than we currently give it credit for.

Is Climate Anxiety a Recognised Medical Condition?

Climate anxiety is not currently recognised as a medical condition or mental health disorder in the diagnostic manuals used by health professionals, and many experts caution against medicalising this entirely understandable and expected response to the looming environmental crisis.

This last piece of information might surprise you: if climate anxiety is so widespread and potentially harmful, why wouldn’t we want to medicalise it as soon as possible? Surely by medicalising it we could make treatments more readily available and get people on-track to feeling a bit better?

It might be true that by making it an “official” condition, you’d open up avenues for people to pop a few (prescribed…) pills that would take the edge off their existential dread. However, Aussie data shows that a much better long-term plan could be letting eco-anxiety grow into “eco-anger”…

The Long Overdue Rise of Eco-Anger

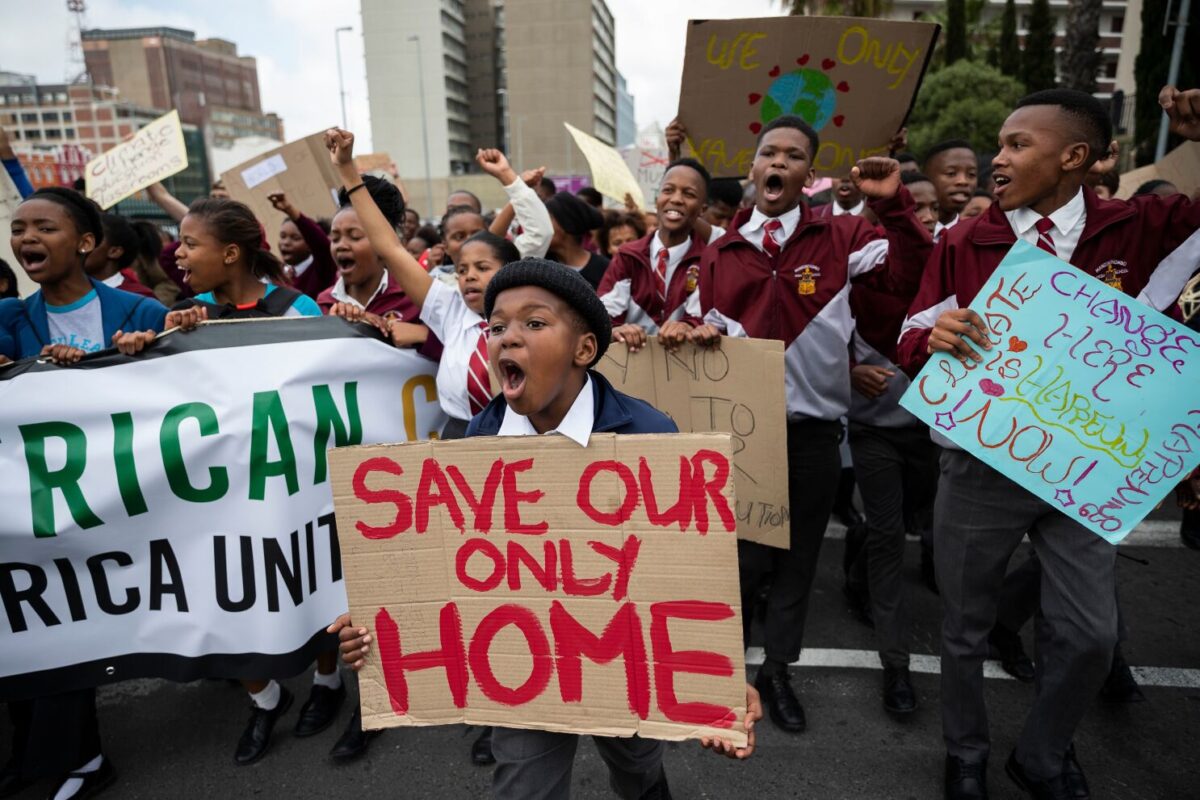

By encouraging the transference of climate anxiety into eco-anger, it not only encourages people to channel their emotions into environmentally beneficial activities like climate protest or activism which, in the longer term, are vastly better for the population as a whole, but it also can lead to far better mental health outcomes for the individuals involved.

When people engage with the crisis, rather than let it paralyse them with totally understandable fear, not only will they feel better themselves, but might actually make the crisis itself a little bit better. If we make the feelings of fear around the climate crisis a diagnosable condition, we risk individualising the problem and placating people through medication, rather than alerting them to the very genuine collective risk and inspiring them to engage with it.

Though it is obviously crucial to support people who support any kind of anxiety – climate inspired or otherwise – through whatever means can best improve their quality of life and negate threats to their well-being and safety, by encouraging those suffering from climate anxiety to channel their fear into anger and then into action, we can far better equip ourselves to navigate the challenges of a fast changing crisis.

So there’s my two cents folks, take it or leave it. What do I care anyway, it’s not the end of the world…