The blossoming world of psychedelic therapy could change the face of mental health treatment. With trials returning continually stronger evidence for the benefits of psychedelic therapy in treating a number of conditions including depression, OCD, and PTSD, the move of psychedelics from fringe hippie fun to mainstream medicine seems nearly inevitable… But when, if ever, will normal Aussies be able to access it?

The world is in the midst of a mental health crisis, and Australia’s troubles are particularly acute: nearly half of Australians will experience mental illness in their lifetime, 80% of Aussies now report poor mental health in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, and Australia has the second-highest per capita use of antidepressants out of all the OECD countries.

All in all, this is thought to cost the Australian economy around $220 billion per year, not to mention the incalculable effects on people’s well-being and quality of life.

RELATED: $25k For A Pill? Psychedelic Therapy Could Become Australia’s Most Expensive Drug Habit

That’s why when news broke last month that the TGA was approving MDMA and psilocybin for clinical use, it was enthusiastically welcomed by millions of Australians, as well as researchers, practitioners, and interested parties around the world.

News outlets around the world splashed the headline across their front pages and homepages alike, but what exactly is so great about psychedelic therapy? And how easy will it be for normal Aussies to access this kind of treatment?

DMARGE spoke with world-leading psychedelic expert Professor Robin Carhart-Harris – Head of the Centre for Psychedelic Research, Division of Brain Sciences at Imperial College London – who has pioneered some of the most important breakthrough trials in using psychedelics in the treatment of mental illness, and gave a recent talk in partnership with Mind Medicine Australia.

One of the first things Professor Carhart-Harris pointed out was the etymological roots of the word “psychedelic”, as a means to illustrate what people hope to, and shortly could, get out of using these drugs in therapeutic settings.

Psychedelic Therapy 101: How Does Psychedelic Therapy Work?

The word “psychedelic” was first brought to prominence by an English psychiatrist, Humphrey Osmond, who combined two ancient Greek words: psyche – “soul” or “mind”, and delos – “to manifest” or “reveal”. At the most basic level, this is what the psychedelic experience promises: a chance to reveal the inner workings of your mind and, if properly guided in a therapeutic setting, re-wire it for the better.

Before we get into it, Professor Carhart-Harris was quick to point out that, though clinical evidence grows increasingly strong for his theories, many of his ideas still fall under the technically-hypothetical category. Regardless, we’ll distil them as clearly and simply as possible:

Your brain has a characteristic called “plasticity”. This is its ability to change and re-mould itself in light of certain conditions. For example, in a clinical trial carried out on mice, when you pinch their tail, the brain instantly shows a huge amount of plasticity by releasing vast amounts of serotonin to help the mouse survive and escape the current situation.

The problem many humans have, however, is that their brains naturally resist their own plasticity as a means of exerting greater control on their surroundings and their experience of them. Professor Carhart-Harris calls this process “canalisation”: much like a canal that relies on a dug-out trench to direct water down a prescribed route ad infinitum, the brain relies on deeply entrenched behaviours and patterns of thought to survive day-to-day.

Examples of this include the negative biases seen in people with depression, OCD sufferers’ fixation on contamination and regulated behaviours to control the perceived contamination, or the way that people with eating disorders become obsessed with their bodies and controlling the calories that go into those bodies.

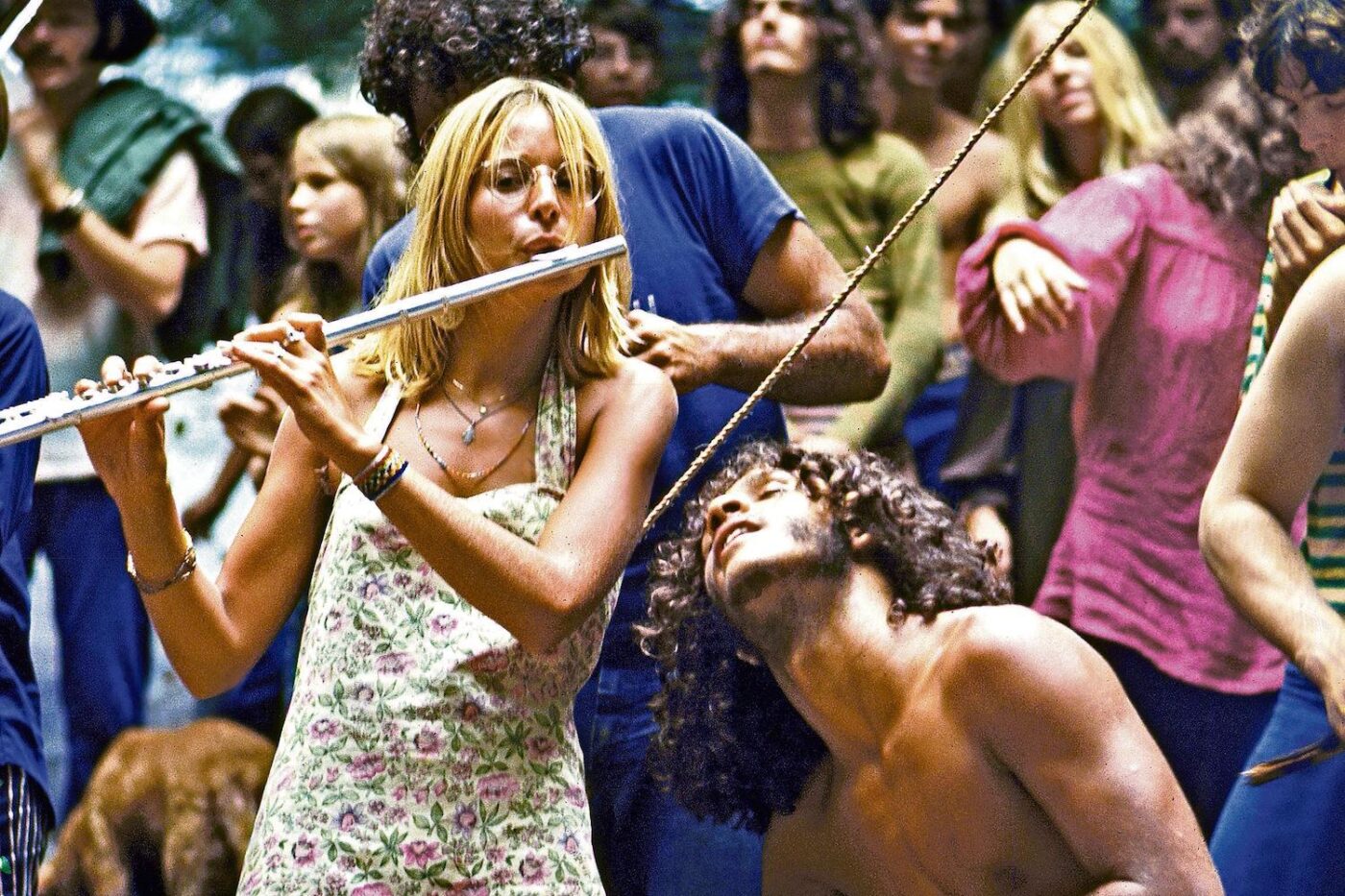

Psychedelics have the ability to “hijack” the brain’s natural plasticity and exploit its ability to change in order to break out of these obsessive and repetitive behaviours. When you ingest psychedelics (in a highly regulated, therapeutic setting, not in a festival tent with your old schoolmates), the levels of communication within the brain’s cortex multiply massively and allow new pathways of thought and behaviour to open up, increasing the chance that you can break out of your more damaging behaviours.

One of Professor Carhart-Harris greatest observations was about the results seen from psychedelic therapy versus those from SSRIs (the standard first-call antidepressant medication prescribed in many developed countries): the expectancy of someone who ingested psilocybin had very little impact on their therapeutic result compared to someone who takes SSRIs.

In other words: for SSRIs to work, you have to want them to work. With psilocybin, it makes no difference. SSRIs are, to some extent, a placebo. Psychedelics may not be, making them – hypothetically – a much more effective kind of therapy.

Will Australians Be Able To Access Psychedelic Therapy?

The TGA (Therapeutic Goods Administration) has rescheduled psilocybin and MDMA from Schedule-9 “prohibited substances” to Schedule-8 “controlled medicines”. With this rescheduling, psychiatrists who are given approval will be able to prescribe psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression and MDMA for PTSD from July 1st 2023.

So in theory, Aussies will be able to access these treatments pretty soon. But there are a number of factors that might impact how available medical psilocybin might be. First, unsurprisingly, is cost. The reason SSRIs are so readily prescribed around the world is that they’re cheap.

Obviously, producing any medicine at scale comes with a cost, but popping out a few pills is a lot cheaper than the facilities required for psychedelic therapy: a controlled trip can take around six hours and requires an isolated, fully furnished room as well as one (preferably two, for safeguarding reasons) practitioners in the room alongside the patient. That space, time, and labour are all extremely costly.

This means that when the rescheduling comes through, the treatments will likely be the preserve of the well-to-do who can afford extended sessions with private practitioners. It’s highly unlikely that the medicare-funded public health provision will be willing to allocate the required resources to this therapy when cheaper alternatives, such as traditional CBT therapies as well as SSRIs, exist.

That is, unless (or until…) psychedelic therapy’s results become so effective that it becomes cheaper to treat mental health issues with one or two psychedelic sessions rather than extended treatment plans via traditional methods.

There’s also the matter of training: practising psychedelic therapy properly requires complex and continuous training, and the question of who will be first to apply for and complete this training remains to be answered.

However, we hypothesise that it’s likely to appeal to privately practising, costly, and potentially mystically-inclined practitioners who already have the time, resources, and inclination to adopt the practice, rather than the overworked and underfunded doctors working in public-facing medicine.

The Bottom Line

Psychedelics offer an immensely promising and exciting avenue for mental health treatment. Though they’re set to be rescheduled in Australia, a great deal more study and training is required before it can be rolled out on a wider scale. But, when it does reach a wider audience, there are important questions to be asked about who will be able and inclined to access it, and who’ll be left behind.

As with so many things, the fear is that the well-off and idle may have first dibs whilst the most vulnerable and in need are left behind… But this, as with so much around psychedelic therapy, remains to be seen.

Professor Carhart-Harris’ lecture, along with supporting slides and data is available on request from Mind Medicine Australia.